To Rebuild or Not to Build,Bornplatz Synagogue in Hamburg

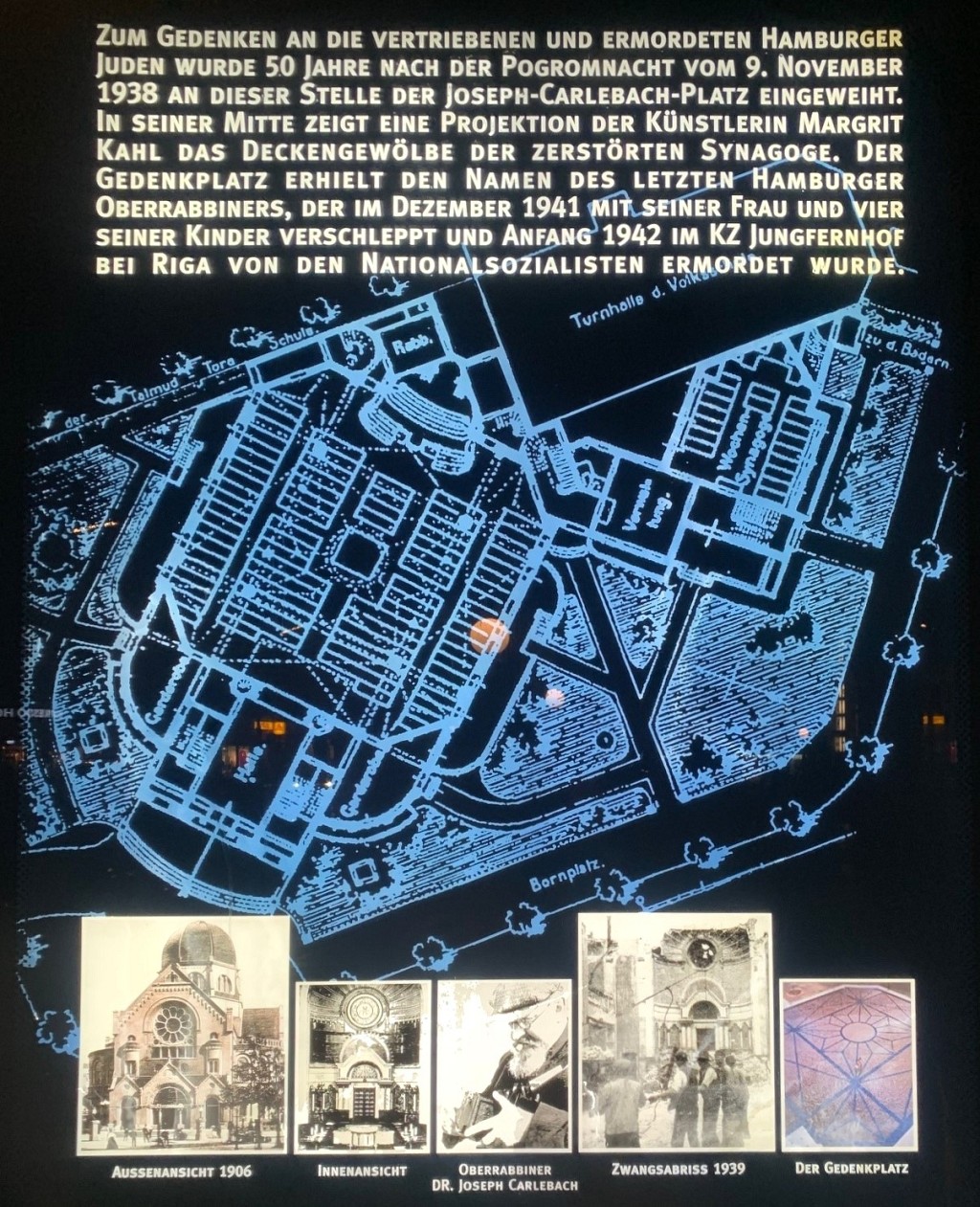

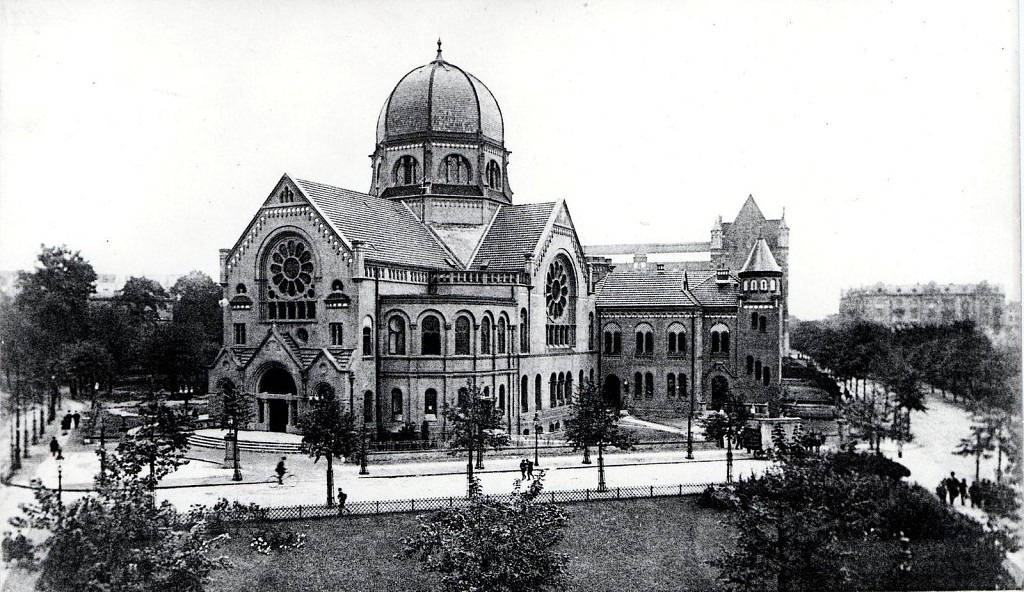

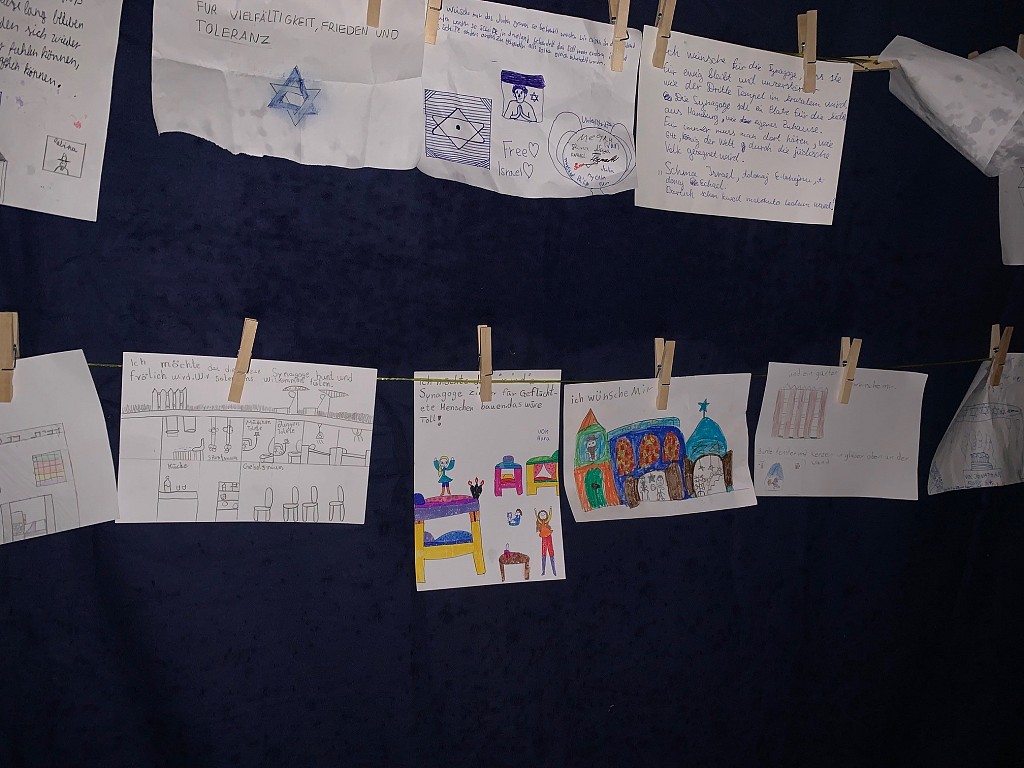

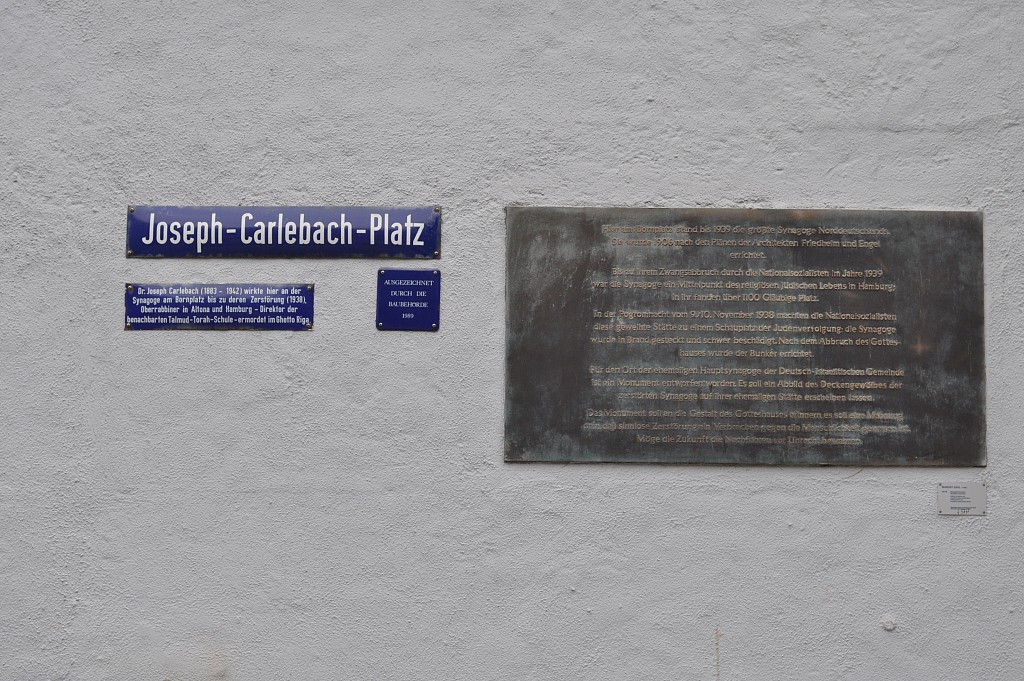

In a span of just six years between 1939- 45, six million Jews were murdered across German-occupied Europe, which is around two thirds of Europe’s Jewish population at that time. A turning point in history that has reconfigured our understanding of human nature, redefined our interpretation of politics, and most importantly, it shaped the way we remorse over our targeted heritage.Since 1939 members of the Jewish community in Germany were constantly attacked, their assets were confiscated, and their buildings and sacred monuments were demolished. In fact, targeting the Jewish community started a decade prior to those disrupting events, precisely in 1929 after the global economic crisis followed by aggressive anti-Semitism calls to boycott anything that is Jewish. In that time Hamburg was the second largest city in Germany with a population of one million citizens including 20.000 Jews. This minority flourished and managed to establish a successful economic base for the Jewish population that aimed to have equal rights within the Christian majority. To reinforce that purpose, this community established what was referred to as the grandest synagogue in the whole north of Europe with space for 1200 worshipers: the Bornplatz synagogue. It is a space that had a high emotional significance for the Jews as a building through emphasizing the political and legal equality for that minority. Affected by the disrupting events in 1938, this neo-Romanesque temple was attacked and bombed, not because it was just a space for the Jewish community, but because it was the core of their community. Ordered by the German Nazis, the Jews fell under duress to demolish their cultural and religious symbol on their own expense, which was a clear message from the aggressors that Jewish history is on its way to be obliterated. Four years ago in 2018, we extensively followed the rapid discussions among the Jewish community and the state authorities in Hamburg concerning the destiny of the vacant land that was once occupied by Bornplatz synagogue. The current debates revolve around whether to resurrect the old structure as how it was, or to build a contemporary building for worshiping, or to keep it vacant and leave this constant pressure of the ‘culture of guilt’ to overcast the German society. Through interviewing key members of the Jewish community and the German authority, we try to answer some pivotal questions: In what way are socio-political changes effectively incorporating into tradition and its narratives? And how does this resonate with the new existence of the Jewish minority especially after the new waves of Arab immigrants in 2015 coming from areas that have constant dispute with the Jews? Do we, as architects and planners, need to embrace a new approach to create spaces that allow different people from different orientations to come together and defeat this trauma? Answering those questions might help us figure out if we can find new meanings through contemporary reinterpretation and reuse of traumatized heritage and vandalized architecture.

- Location

- National University of Singapore

- Year

- 2022

- Status

- Paper / Conference

- Author

- Bedour Braker, Ph.D.

- Type

- Conference

- Organiser

- IASTE & National University of Singapore

- Presented

- 13- 17 Dez 2022

- Link

- https://iaste.org/iaste-2022-singapore/